A Street Named Santa Claus

Part 1--My Childhood Home in Santa's Little Village

This is a Christmas story I’ve wanted to write for a very long time. Enjoy and please share! --Ken

A Street Named Santa Claus

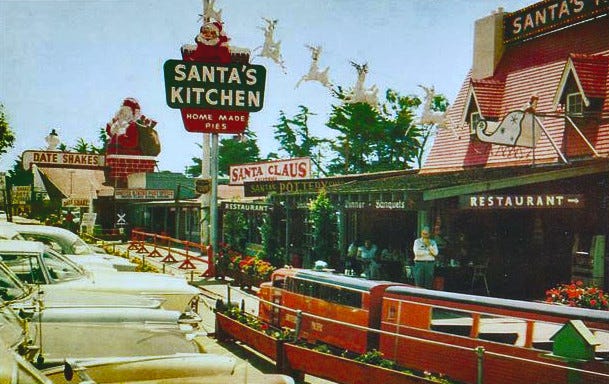

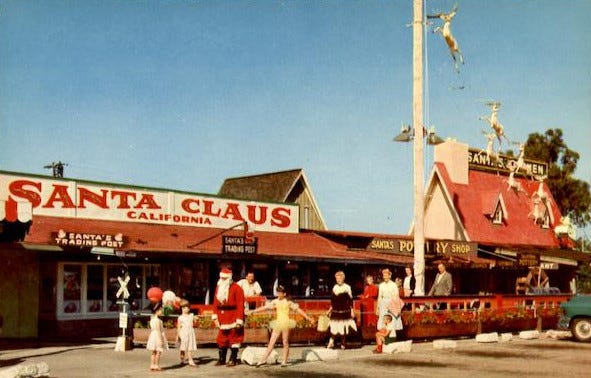

Imagine being a five-year-old kid living in a little town by the ocean, and even though it’s almost always sunny and warm, all the buildings are decorated for Christmas. Santa’s sleigh and a beautiful team of reindeer are perched high upon a rooftop so steep even a mouse couldn’t get up it. Nearby, you see a toy store and Frosty’s cafe, the roof adorned with a giant snowman with a pipe and a fine, black top hat. The aroma of delicious food slipping from the windows and making you hungry.

Next door to Mr. Snowman, you lean your little head way back to see a larger-than-life Santa Claus, with a bulging bag of toys and gifts on his back. His arm is raised almost to the clouds, waving to the world from the great chimney of a candy store. And imagine there are bright lights and glittering ornaments, striped candy canes and Christmas trees all over the place! Even the street you live on is named after Santa Claus.

And in the middle of it all, you find a miniature, kid-sized choo-choo train you can actually ride on! There are ballerinas and elves and other kids your size, some of whom are actually your siblings, your cousins and your friends, all of you riding together through a mysterious tunnel and circling all the way around the village. And the kind engineer in his striped bib overalls, or maybe even Santa himself, says if you’ve been nice, you can hop on and off the train just about anytime you like.

Imagine that all this joy to a five-year-old lasts and lasts, not just for a few days or weeks at the end of the year, right around the holidays, of course. But, in fact, you are surrounded by this magical Christmas universe all year long.

I can easily imagine such a thing, because that lucky five-year-old was me.

At Home in Santa’s Little Village

In the mid-1950s, my grandparents, who everyone called Dee and Dutch, decided they’d had enough of the cold and snowy winters of Utah, and were moving the family to the warmer skies and palm trees they’d been dreaming of in sunny Southern California. They were moving to Santa Barbara.

They’d also heard about a unique village taking shape a few miles down the coast near the town of Carpinteria. It was called, simply, Santa Claus. And why not? If there could be a Santa Barbara, Santa Monica, Santa Maria, Santa Cruz, why not a Santa Claus?

Its story can be traced to a 1940s orange juice stand known as the North Pole--a place for weary drivers with no AC to pull off the highway and cool off. By 1948, its new owners, Pat and June McKeon, had a much bigger idea. They renamed the place after the big man and began to expand the little strip into a village.

Adjacent to the Pacific Coast Highway, and later U.S. 101, Santa Claus became a place where visitors could enjoy Christmastime all year long. To my grandparents, it was a fabulous concept. Maybe they could operate a small gift shop there?

The most prominent landmark at Santa Claus was the big guy himself. An eighteen-foot tall, 3,000-pound Santa perched on top of the candy store, aka the Date Shop. A May 30, 1999, L.A. Times article explained how he came to be:

In 1950, a motorist down to his last dollar pulled into the Santa Claus fruit stand with five children in tow and offered to build a Santa for $500. The result was the towering concrete-and-chicken-wire statue that has stood atop the same chimney for almost five decades.

By the late 1950s, I’d gotten to know that Santa quite well. Together, Santa, the reindeer, the Snowman and the choo-choo formed a familiar wayside along U.S. 101 for travelers near and far. The notion seemed well received overall, though some might have shed a tear that it never quite gained the kind of traction that many had hoped for. Many blamed the completion of U.S. 101 itself, which rendered the old Pacific Coast Highway essentially a frontage road. Still, my grandparents thought it worth the gamble.

In Salt Lake City, Dutch had run a corner grocery market for years and proved himself a competent businessman. He even opened the first true deli in the city. Dee was very good with numbers, finance and property matters. She played the piano and was quite handy at fixing things. (Later in life, she studied auto mechanics so she could save a few dollars crawling under her car to change the oil.) Operating a grocery had been a great experience for them, but it was hard work. A gift shop at Santa Claus would be a welcome change.

From a kid’s perspective, Dee and Dutch were wonderful grandparents. When they left Utah for California, my mother, who was recently divorced, and my older brother, Skip, and I stayed at their house in Salt Lake for a time. I was just two when Mom remarried. We soon moved south to a small farm in Draper, Utah, where Skip and I gained two new baby brothers, Kelvin and Gailen--plus four little lambs and some chickens. Our next door neighbor was the Utah State Prison.

In May 1957, Dee and Dutch signed the lease for a shop at Santa Claus and purchased the inventory. It was named Santa’s Trading Post. The shop was located between the candy store, known then as the Date Shop, and a shallow wishing well where people tossed their coins for good luck. We must have missed them a lot, since within a year or two, our family packed up and joined them in California.

When we first visited Santa’s Trading Post, it seemed enormous to me. It was filled with everything imaginable--candles, seashells, glass figurines, coconut shells with funny faces, postcards, key chains, puzzles and games, Christmas ornaments, and mugs and dinner plates with pictures of Santa on them. As a curious five-year-old, I would search the tables, shelves and baskets for hidden treasures.

Dutch would let me sit on a high stool by the tall, ancient cash register, keeping guard while he was in back messing with the merchandise. I quite enjoyed pushing the register buttons with the numbers on them and watching the drawer spring open. The train tunnel was right next door to the shop. You could hear the bell ringing whenever it went by.

It was also my job to sort through the coins and place the older ones like buffalo nickels in a special box. I’m sure other grandkids in the family had similar jobs whenever they dropped by. Dutch was most definitely a kid-hugger. I can still feel the bristles on his cheek when I think about him.

I vaguely recall that when I was off duty from my psuedo-cashiering job, I would fish coins from the wishing well, perhaps pocketing a nickel or dime when no one was looking. Sometimes a man would sit by the waterwheel near the shop, and for a quarter, write your name on a grain of rice. I wanted one for myself, but twenty-five cents was just too darn expensive. Close by was what I think was called a Mutoscope. You could insert a nickel and turn a crank to watch a short movie made with flipping cards.

Dee and Dutch apparently had some run-ins with their landlord. Rent was based on a percent of sales, and they noticed the man looking through the front window, presumably to see if they were ringing up all the sales. The cash register kept a daily tally. The man would even ask exiting customers (allegedly) if their sale had been properly rung up. They found the man’s behavior annoying.

At some point, another building came up for sale, but the owner refused to sell to the nosy landlord. She offered it instead to my grandparents at a good price. They were elated to buy it and open a new shop there. It was located at the north end of Santa Claus Lane, the main street of our Christmas village. This shop was also called Santa’s Trading Post, and the original one was closed down when the lease expired.

Dee and Dutch often drove Volkswagens, a bus and a Beetle, and I would sometimes ride with them to gift shows where they would browse the latest goodies and dicker on prices to restock the inventory. Maybe it was in Thousand Oaks where I first watched a woman making candles by dipping strings into different colors of melted wax. I was struck by how clever she was.

There was apparently a lot of room in the back of the new shop, and even a bathroom and a kitchen. So my parents and my grandparents decided that our family might as well live there. I never quite understood the arrangement, but I recall that my stepdad had some kind of back injury and was unable to work for a time. I think Dee and Dutch were helping us out. Later, he recovered enough to begin driving a ginormous furniture van for North American. Sometimes he would be away for weeks at a time, leaving my mom with four boys to manage single-handedly. We were surely more than a handful.

The new Trading Post had the added fringe benefits of snow cone and cotton candy machines, a corn dog rotisserie and a peanut roaster just inside the entrance, which is pretty much how you spell h-e-a-v-e-n to a kid. The cotton candy was pure magic, by the way it seemed to appear out of nothing. And those warm, roasted peanuts just begged for little hands to rip them to pieces.

Sometimes, we were supposed to be useful. I would help Dutch with packages that needed to be tied with string and mailed off to someone. He taught me that before you tie a bow, give the strings an extra wrap and the friction will hold the knot in place. That way you don’t need a second person to hold their finger on it. I’ve used that technique ever since, even to tie my bathrobe.

My friends were almost all girls around my age: two were close cousins, two others were twins with cute pixie hairdos and blue dresses who lived nearby. Other than my brothers, my only man-friend, so to speak, was Stevie. His dad ran the Frosty’s with the Snowman on the roof. It seemed that Stevie and I had nearly 24/7 access to ice cream cones and sprinkles, plus the occasional hamburger. We were not so fortunate at the candy store, where handouts were mostly verboten. Still, we had great fun watching the taffy machine quietly do its stretchy thing, on and on and on.

If the weather was warm, as it often was, we could hop across the big, scary railroad tracks behind the shop, and clamber over giant boulders to get to the beach. From there, you could splash and run forever. I seriously objected, however, when my big brother or one of the grownups picked me up and carried me into deep water. Body surfing in a waist-high, two-foot surf was more than enough excitement for this little guy.

There were also sprawling iceplant beds and deep sand behind Santa’s Trading Post, where we could search for giant sand beetles and dig trenches and hide. If we were very lucky, a real, thundering freight train might rumble by pulling a white caboose. My brother called it The Ghost. We would watch every train we could, because just so often we actually got to see the rare caboose. The sighting would earn us some important bragging rights. It was almost as much fun as leaving a penny on the tracks to see how it got squished. That is, if you could find it after the train was gone.

As a maturing, baggy-pants post-toddler, I’d somehow missed kindergarten, and started the first grade at age six in 1959. I rode the school bus with my twin girlfriends from Santa Claus to Mrs. Constantini’s classroom in Carpinteria. I barely remember doing three things there: learning to play dodgeball, getting scolded for wetting my pants at recess, and singing Let’s Go Walking in rounds. Who knew that decades later I would author four guidebooks to walking and hiking in Washington state and Washington, D.C. The song still plays in my head at times when I’m out hiking alone.

Though our dad was away a lot, he must have been doing pretty well, for he soon bought us a house. It was a rambler in Port Hueneme, just outside the navy base (he’d served in the navy during WWII). In the summer of 1960, we gathered our things and left Santa Claus to live in our new home. Skip and I, ahem, helped Dad build a cinder block fence around the back yard, and a sand pile to play in.

I became a second-grader at Sunkist Elementary. The memories are vague, but I think we learned to write in cursive there and watch baby chicks hatch from their eggs. I also know that in class one day we all got to vote for the next U.S. President. Even though my name was right there at the beginning of “Kennedy,” I voted for Nixon, because we both had a cool “x” in our last name. Clearly, I was an informed voter.

I still remember our address, 825 Thayer Lane, and Dad’s enormous Mack truck parked at the curb. And the familiar bell of the doughnut truck every Sunday morning. I’m sure there was an ice cream truck cruising through the neighborhood too, but it’s the lemon-filled, raised doughnuts I remember most. I also remember that Mom, after bearing four boys, finally got her wish for a daughter that year: my new baby sister, Beth.

Though we had departed our perennial Christmas village at Santa Claus, we were still just a short drive away. We often went there for the usual fun, or we drove to Santa Barbara to visit the cousins and grandparents. If we happened to head home from Santa Barbara in the evening, Grampa Dutch would give Mom a little cash so we could stop for ice cream on the way home. He always worried about us making the drive in the dark. So once we were home, Mom would place a collect call to Dutch, which he would decline, of course. It was Mom’s signal that we were safely home.

We had a couple of good years in Port Hueneme. In the third grade, I recall chasing after two new girlfriends, Sandy and Rosemarie. The latter I nearly tackled at full speed once so I could kiss her on the hand.

A couple of times our entire extended family went to Disneyland when the Matterhorn bobsled ride was brand, spanking new. And we got to sit on the sidewalk at the Rose Parade to watch all the floats go by.

So life goes on, as they say. My family eventually moved back to Utah. We grew up. Mom pushed out one more little brother, Dean, and one more sister, Arlie. Gailen went back to Santa Barbara to stay with our grandparents for a while. When my older brother, Skip, the rock of my childhood, finished high school, he joined the Marine Corps and shipped off to Vietnam. I was extremely relieved when he returned safely in 1970. He was soon engaged to be married in Salt Lake.

By then, my parents had relocated us to Washington state, again on a little farm, an hour north of Seattle. It was too much for us all to travel to Utah for the wedding, so just my parents went, while I looked after the clan. Dee and Dutch certainly weren’t going to miss the wedding of their first-born grandchild. They closed things down at the shop, and Dutch drove Dee and Gailen back to Salt Lake for the big event. They checked into a motel that tragic evening, for by morning, Dutch was dead. With no warning at all, he’d just passed away in his sleep.

The death of my grandfather, of course, was a great shock to everyone, and compounded by the fact that Dee had already lost her aging mother six weeks earlier. She now had both a funeral and a wedding to attend to. Yet she carried on through with her indefatigable spirit, and soon returned to Santa Barbara.

Alone, she made her way back to the shop in Santa Claus, feeling quite lost without Dutch around to help guide the way:

I unlocked the door, walked in and looked around. Now what to do? I sat down . . . I cried a lot . . . At times I would say, “Come on, Dutch, tell me what to do.” . . . Somehow I got the job done.