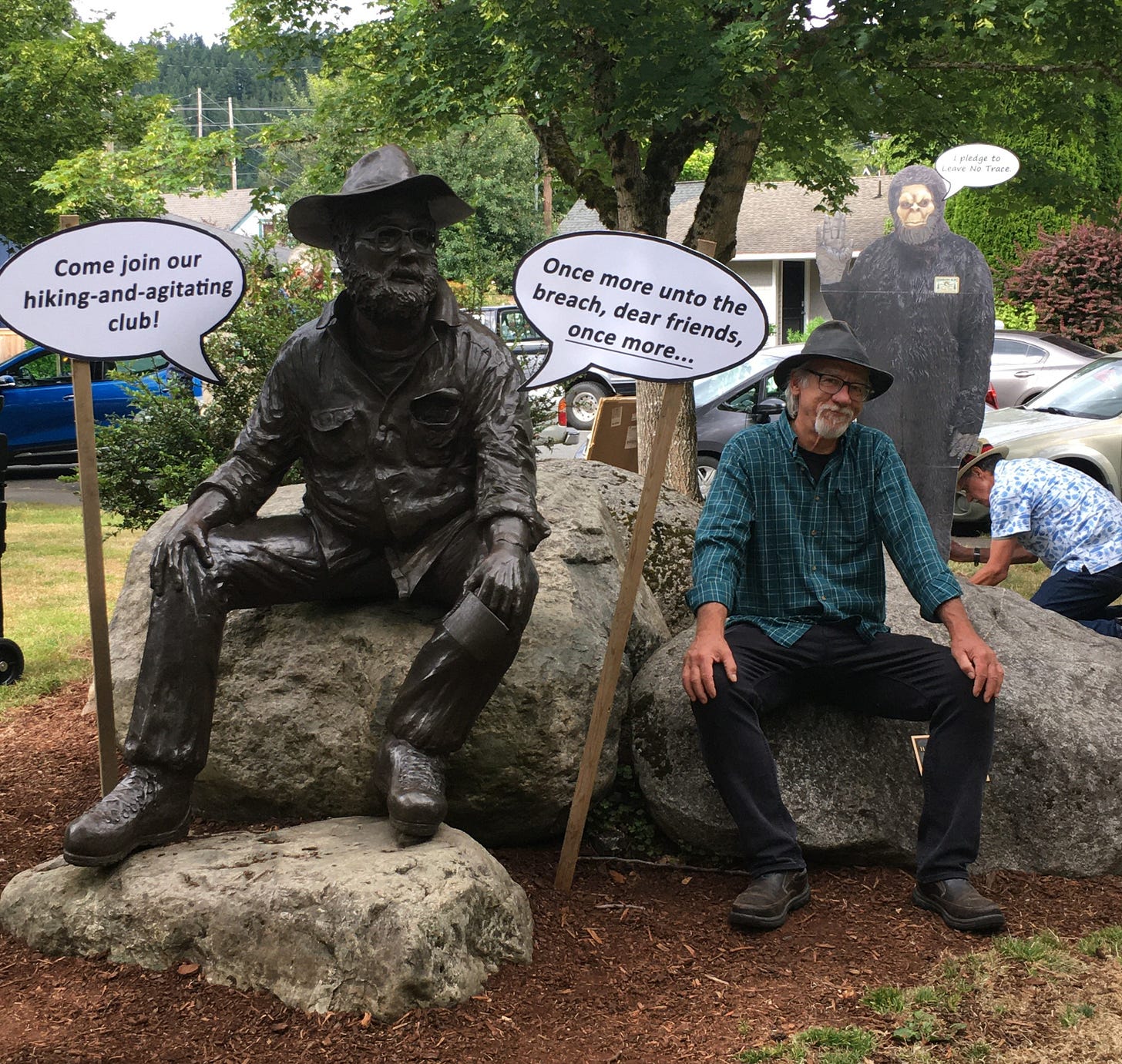

On Thursday (July 10), Kris and I attended a 100-year birthday bash in Issaquah for the iconic guidebook author and conservationist Harvey Manning. So glad we did. His actual birthday is July 16, but no matter.

The event was organized by the Issaquah Alps Trails Club and was held next to the larger-than-life Harvey-on-a-rock statue downtown. If you love trails and wilderness, steer your buggy off I-90 next time you pass through, then take a look at Harv’s likeness and say thanks for all the good work he did. And you may as well enjoy a hike in the Alps while you’re at it, and maybe a dinner out to soak up some of that salubrious Issaquah vibe. (For the statue, GPS yourself to the Issaquah Community Center and walk a block north on the wide path.)

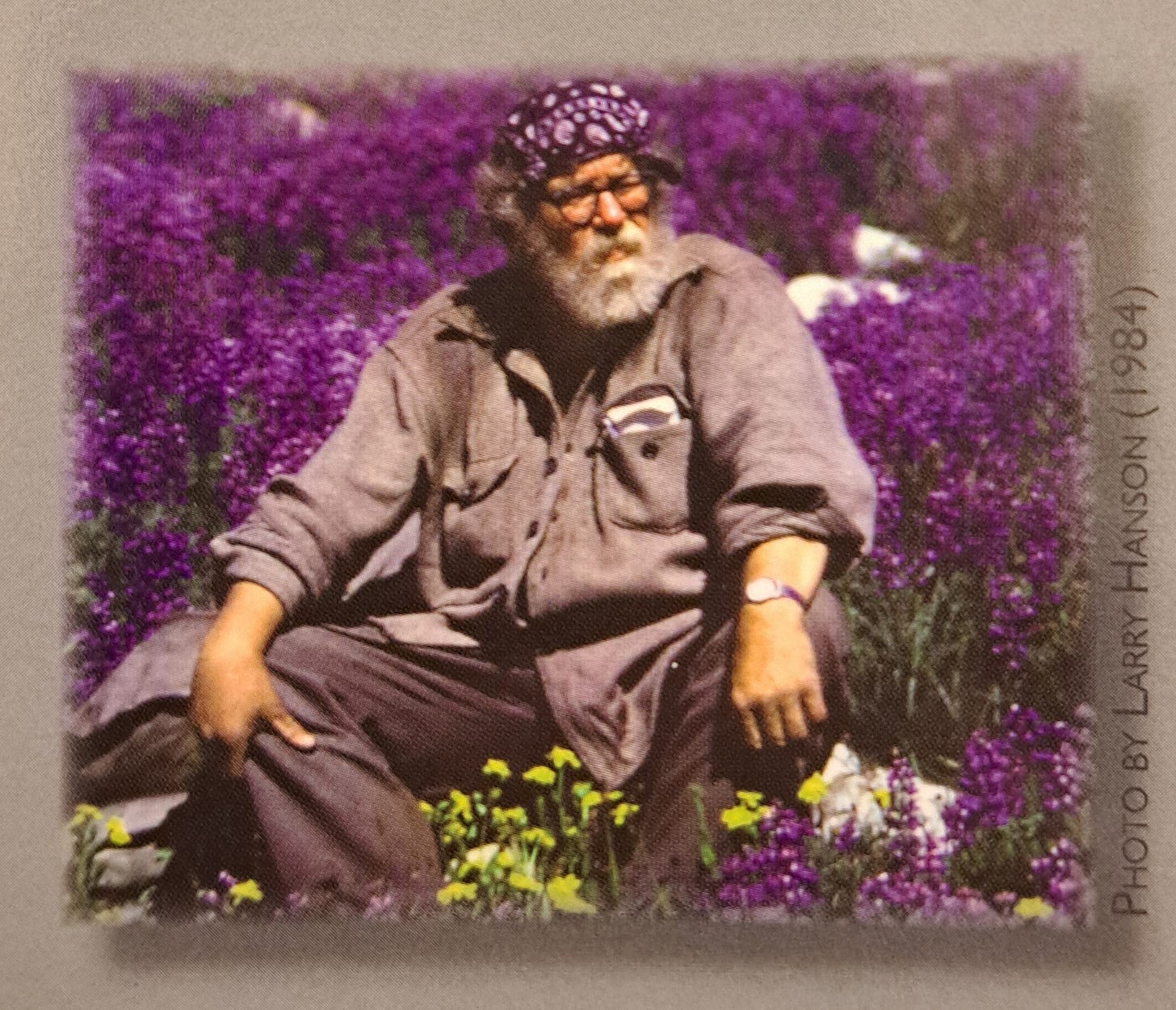

I was lucky enough to know Harvey and work with him on a variety of park and wilderness issues over two decades, mostly in connection with the North Cascades Conservation Council (NCCC). I first met Harvey at a trails conference in Seattle in the early 1980s. I was a pretty avid hiker and climber already and knew his books well.

At the conference, I noticed over in a quiet corner, a man was sitting alone at a round table with a few empty chairs. On second glance I realized it was Harvey, arms folded, wearing his trademark hat, and those unmistakable, dark-rimmed glasses. I sheepishly wandered over and sat down, utterly clueless how to converse with the guru himself. Lucky for me, he had no problem doing most of the talking. I might have spoken ten words, but he engaged nonetheless, smiling gently behind a whitening beard.

Harvey had already been a longtime member of the board of the NCCC when I joined around 1984. I’d been active with a Bellingham group advocating (against all odds) for a new wilderness area around Mount Baker. Somebody got wind of it, and because they needed somebody on the board from “up north” I was invited to join. I was still a newbie at this saving-the-wilderness thing, but I loved the idea of it and was flattered to be asked.

The infrequent meetings would take place in someone’s living room, me the inadequate stranger among not only Washington’s conservation heavyweights—Pat Goldsworthy, Poly Dyer, Phil and Laura Zalesky and others—but also on occasion by the late-great Dave Brower, former Executive Director of the Sierra Club and the primary protagonist in John McPhee’s preservation-versus-development eco-page-turner Encounters with the Archdruid (1971). Brower was also among those who were central to the creation of North Cascades National Park.

Brower’s 31-minute film, Wilderness Alps of Stehekin (1958) brought national attention to the cause and is still well worth viewing. The soundtrack is a hoot. What’s not a hoot is the tremendous extent of glacial retreat that’s obviously occurred since the film was shot in 1957. Thanks to the great work of Brower and the NCCC, as well as the political leadership of Senator Scoop Jackson and Governor Dan Evans, and the efforts of countless others, North Cascades National Park became a reality in October 1968.

I vividly recall a few early NCCC meetings, the self-deprecating absurdity of clueless me sitting on a couch, stiff as a brick, scrunched shoulder to shoulder between Dave Brower and Harvey Manning. A dozen years later, I managed to leverage that momentary couch togetherness in persuading Brower to scribble a back-cover blurb for a little book I wrote on forest conservation in Chile.

For Brower and Manning both, protecting wilderness was far and away their highest priority. Films, guidebooks and coffee-table books were critical tools for building public support to protect what deserved to be protected before the “barbecuers,” as Harvey would say, spoiled it all. As an agitator, he learned how to critique right up to the edge of civility, and a little past it some might say. His more fiery remarks were often seasoned with a glint of the eye and a dash of humor. He described his early evolution thusly:

In my immediate circle of mountain companions, “conservationists” were so notably rare as to be objects of curiosity, and I used to consider their sermons on the mount as eccentricities to be tolerated and enjoyed as one enjoys a friend’s odd devotion to yodeling or smoked oysters . . .

But he took those sermons to heart, writing:

They’ve logged my memories, they’ve cut me adrift from my human youth, they’ve left me no changeless wilderness to connect the ‘Whatever-I-was-then’ to the “Whatever-I-am-now.’ They made me what I am today, those Devils, and I hope they’re satisfied. Because now they’re going to get it.”

For people to be inspired enough to want to join the cause, to save the wilderness, they also needed to experience these places firsthand. Enter guidebooks. At The Mountaineers club in Seattle, Harvey led the effort 70 years ago to begin a publishing arm that’s since become the premier source of hiking guides and outdoor books in the Pacific Northwest and beyond. Freedom of the Hills came first in 1960. Now in its tenth edition with nearly a million copies sold, Freedom remains the principal textbook for newbies and intermediates taking classes to learn the ropes of mountaineering.

Working with Brower in 1965, Harvey authored the influential Sierra Club coffee table book, The Wild Cascades: Forgotten Parkland. Soon after, the first official Mountaineers guidebook, edited by Harvey, was released in 1966: Louise Marshall’s 100 Hikes in Western Washington. The legendary twin brothers Bob and Ira Spring provided the photos. The book was a huge success and catapulted the club into the outdoors publishing world. Louise and Ira were also co-founders of the Washington Trails Association.

Together, Ira and Harvey would soon be on a roll producing informative, entertaining and inspiring hiking guides spanning over a thousand miles of trails and millions of acres of wild country. By 1971, the club had published guides to Mount Rainier, the Olympics, North Cascades, South Cascades and even the Alpine Lakes before it was officially designated as wilderness by Congress. New titles and editions seemed to materialize every year.

By the 1980s, conservation-oriented guidebooks by Manning, Spring and others played perhaps an underappreciated role in helping to win nearly three million acres of newly designated, big-W Wilderness across Washington State. Some of that was within existing national parks, but many of the 19 newly-protected wild places, such as the Mount Baker, Noisy-Diobsud, Boulder River and Henry M. Jackson Wilderness Areas were at that time highly vulnerable to logging, mining or other threats. I can hardly imagine accomplishing anything close to that under today’s dysfunctional politics.

I tried to adhere to that guiding principal of protecting wildlands when I started writing my own hiking guides to Northwest Washington in the late 1980s. It seemed a little awkward at first, knowing I was vaguely competing with Harvey “up north.” But I had a vision and went with it. When Harvey autographed a third edition of his 100 Hikes in Washington’s Alpine Lakes for me, he addressed it to “The king of the north.” I took it as a complement, though I later wondered if it might be a subtle warning not to step on any toes down south.

I hadn’t really intended to be a guidebook author, but with all my hiking and climbing, I knew the trails well. Co-workers would approach me for ideas on where to go hiking. Then one day someone suggested that since I knew the trails so well I should write a book. Hmm, I suppose I could do that. Now, five books and 13 editions later, the idea apparently stuck.

Some might argue that guidebook authors may have been a bit too successful, if you’re measuring success by the number of cars at the trailhead or bobbing heads at the overlooks. Overcrowding is now a thing to be sure (and a central theme for an upcoming blog post). On the other hand, there are still large swaths of unprotected wildlands in the Cascades that the public needs to know about. And there are trails worth hiking that somehow don’t make the same ten-best list that everyone seems to be googling. “Ten best” often doubles as a code for “most crowded,” so I encourage folks to do our part and spread ourselves out a bit, carpool more and try to avoid hiking in larger groups. I’ll have more on that in the aforementioned future post.

It’s also important to hit some hikers over the head with a bit of history. Too many trails and protected areas are woefully taken for granted, with little appreciation for all the volunteer sweat and tears, letters, hearings and hard work that go into protecting wild places and keeping them unspoiled and hikable for the generations that follow.

When it comes to the North Cascades, Harvey knew those stories as well as anyone, and wrote it all up as a single volume in the 1990s. When other publishers declined to publish his final book, Wilderness Alps, I stepped into the breach to edit and publish this nearly 500-page history of park and wilderness preservation in the North Cascades.

The manuscript was mostly composed on a typewriter, with scribbles and arrows and chunks of paper literally cut and pasted from once place to the next. Others helped digitize (i.e. retype) it all, and many donated their photos to the book. A committee of NCCC editors further edited my editing, getting us to the finish line in time for the 50-year anniversary, in 2007, of the founding of the NCCC. Sadly, Harvey passed on to the next wild realm in late 2006.

At the birthday party, members of the Issaquah Alps Trail Club, some of whom knew Harvey much better than I, shared stories and memories that were quite wonderful to hear. He coined the term “Issaquah Alps” which helped galvanize the cause of protecting one of the most valued hiking destination close to Seattle. The Alps include Tiger, Squak and Cougar Mountains, the latter being the site of he and Betty’s “200-Meter Hut.”

After the final speaker wrapped up, someone asked when we’d get to sing “Happy Birthday.” That’s all it took to launch a crowd of nearly on-key hikers into song. And there was no hesitation at the end for adding the phrase “and many more!”

Kris and I strolled downtown afterward to snag a fine Thai dinner, before commencing the long drive home to Bellingham.

Happy Birthday Harvey.

If you could use a good hike up a hill, here’s a trail map to the Alps.