Our caravan of dozens of students and climb leaders reached Bellingham at dawn, and continued eastward to the town of Glacier, then up the winding road above Glacier Creek. It was Glacier, glacier, and glacier. A seductive theme was coalescing.

We lumbered up the trail, pausing for a break at the old Kulshan Cabin, just before the meadows. The snow deepened as we trudged upward and out of the forest to our 6,000-foot camp atop the Hogsback at the northwest margin of the Coleman Glacier.

Later, I looked up the name. Edmund Coleman, the glacier’s namesake, was a generation ahead of Easton. He was an accomplished British mountaineer and an exceptional artist who painted dramatic mountain scenes high in the Alps. After an 1858 ascent of Europe’s crowning jewel, Mont Blanc, he made his way to British Columbia, in a quest to explore, sketch, and paint the unknown heights of North America. From a comfortable perch in Victoria, he could sit with his cup of tea and stare at the Great White Watcher from seventy miles away.

In 1866, Coleman gathered teams and made two attempts on the peak. The first was thwarted by a nervous encounter with Native Americans on an approach from the Skagit River. On the second try they were turned back, he said, by a dangerous cornice not far below the summit.

He returned this way again in 1868, in the company of three other climbers and four Lummi and Nooksack Indian guides. As they left Bellingham, Coleman asked the “maidens” in town to pray for them. But one of the women knew better. She replied, said Coleman, “that we should be so much nearer heaven we ought to pray for them.”

Coleman’s team arduously made their way up the Middle Fork of the Nooksack River by canoe, then on foot, with overnight stops at Camp Fatigue, Camp Doubtful, and finally, Camp Hope on Marmot Ridge. After two days of surveying the steeper slopes, teetering seracs, bergshrunds, and gaping crevasses, they moved to a higher camp and settled on a route. Of the four mountaineers, one headed off alone. The others tied into their hemp rope and eventually caught up. Conditions were better now, the weather held, and they reached the summit together on August 17th.

If all went well, we too would ascend the Coleman Glacier, roughly tracing Edmund’s century-old footsteps.

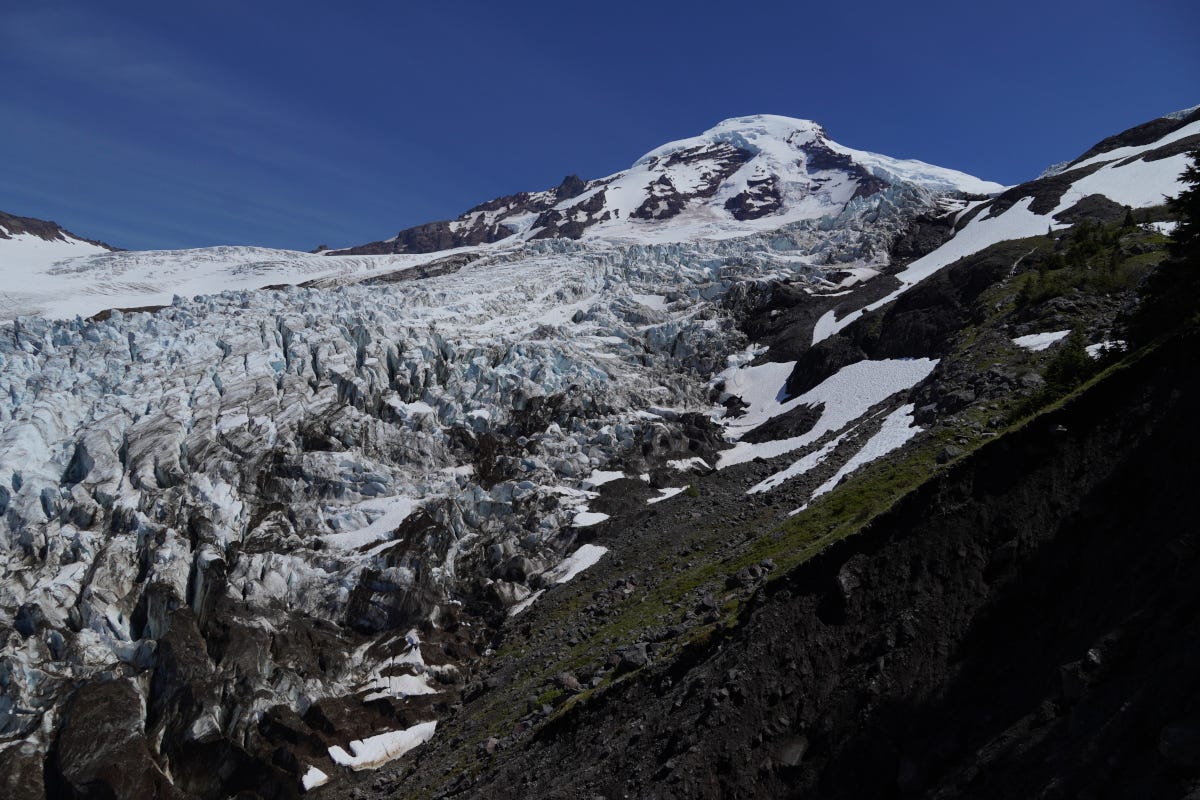

However, we still had other work to do. From camp atop the Hogsback, our necks craned upward to the imposing headwall of rock and ice that towered above several square miles of sprawling glacier, some of it hundreds of feet thick.

Roped up, our team traversed across gentler grades of snow and onto the glacier to find just the right crevasse to carry out our practice. Our eventual chasm was only a few feet across and apparently bottomless. We spent the afternoon quite intentionally lowering one another into the deep, dark void so that we could each participate in the various techniques of getting ourselves or someone else out in the event of a fall. First came self-rescue, then team-rescue with pulley systems and brute force.

The first time I was lowered into the frozen fissure, I could barely hold two things in my head. One was the blue-white walls of ice plummeting into darkness below my feet. The other, the climbing rope leading upward into the light. Though it was securely tied to my harness, it seemed much too meager to be trusting my life to. But if you care for your rope, they said, and use it correctly—and don’t step on it with your crampons—you can trust it like your mom. With encouragement from my fellow victims and rescuers above, I soon learned to relax and enjoy the fun of being in such a forbidden place.

After a good four hours of practice, the session ended and we returned to camp in time to cook supper before dark. We were now on the north side of the same rock ramparts I’d seen from the Easton side, unassumingly referred to as the Black Buttes. They stand as remnants of a much larger volcano that predates today’s Mount Baker by 300,000 years. The Coleman party named the two highest peaks Lincoln and Colfax. Lincoln we know. Schuyler Colfax was an abolitionist businessman who was selected to run as the candidate for vice-president with presidential candidate Ulysses S. Grant. The true summit of Mount Baker is also known as Grant Peak. The two would win the election of 1868, just eleven weeks after Coleman’s first ascent.

We gazed at the pink glow on the Buttes and across the ice and snowfields surrounding us, abask in the last rays of the sun. With the evening stars came a cold, brisk wind that sent us scrambling into our tents and sleeping bags for a few hours’ rest.

Subscriber? Click ‘Next’ to continue . . .