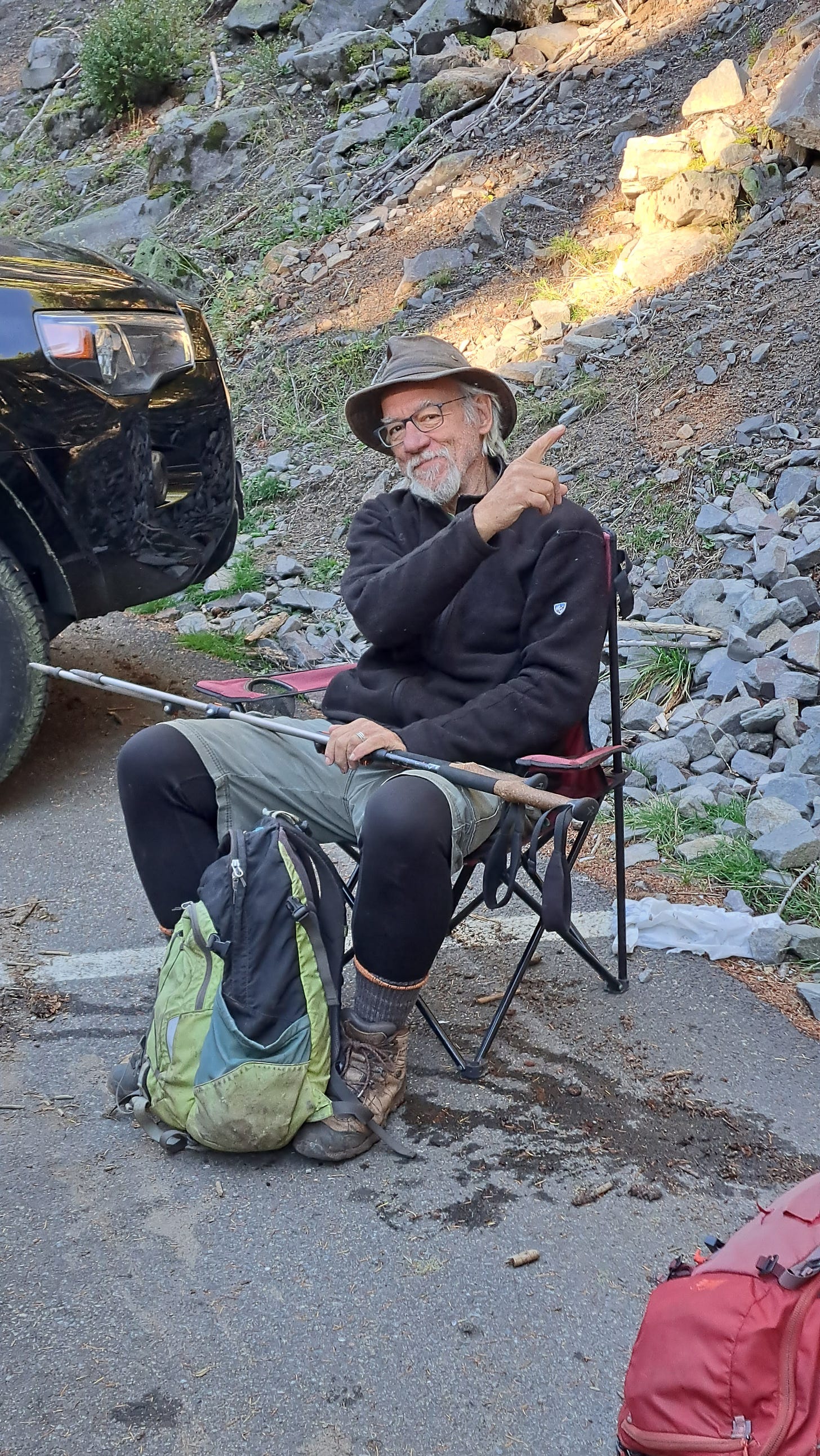

Sitting here in my camp chair at the Comet Falls trailhead, Mount Rainier National Park. Sun through the trees, just now rising above the ridge. Coffee water is about to boil, the pot balanced on my trusty Firefly stove. It hisses on the ground next to my hiking boots. Love those boots, though the leather is coming apart. Gotta remember to take them to the cobbler.

Coffee goes down like the first ray of sunshine through an old forest. A few cars drive by. We’re not the only ones with a big idea today. Mitch is nearly packed and we'll be off to see Comet Falls and Mildred in a jiffy, ahead of the crowd (we hope) on this glorious first Friday in October. I put the chair away and adjust my trekking poles.

Typically, I write these notes after the fact. But today, I thought I'd stop along the way and record our trek as it happens. Neither of us have ever been on this path. And now we’re looking forward to it even more, thanks to an early conversation with the ranger back at the Cougar Rock Campground. He’s a newbie seasonal at the national park, maybe forty and obviously an avid hiker. Been up there? To Comet, I asked? My second favorite hike in the park, he replied.

The hike begins easier than expected, and quickly reaches a hefty footbridge over Van Trump Creek, which we rename Ban Trump Creek. No offense to P.B. Van Trump who climbed the massive peak with Hazard Stevens in the summer of 1870. Their gutsy trek was the first documented ascent of Mount Rainier. The snoozing volcano is known to Native Americans in the region as Tahoma (or Takhoma), the mother of waters (as in ice).

In 1888, Van Trump would guide John Muir, founder of the Sierra Club, to the summit. He then joined Muir in the campaign to create the park. Their work and that of many others resulted in the creation of America’s fourth national park in 1899.

Not only is Van Trump remembered via the creek we’re following, but in a namesake glacier as well, or more correctly, a scattering of glacial ice nestled between the Wilson and Kautz Glaciers on Tahoma's southern flank. Call it a mixed blessing. The National Park Service recently found that P.B.’s glacier has shrunk by nearly half since 2015.

Hazard, too, gets his own namesakes, including Stevens Canyon and Stevens Peak, but not, as some might assume, Camp Hazard. The climbers’ camp is located high on a cleaver just below a calving ice cliff of the Kautz Glacier. The name actually applies to Joe Hazard who climbed the Kautz route in 1921.

A climbing partner and I camped there in the 1980s during a befuddled summer attempt to reach the summit via the Kautz. All seemed promising at 13,500 feet until it began snowing sideways. We turned back. The memory of recrossing a gigantic crevasse on a sagging snow bridge still gives me the shudders. We hustled down the icy slopes, knowing we still had to ascend an active gully littered with fallen ice in order to reach our camp. It’s a good thing we retreated. An intense thunder-snowstorm soon materialized and chased us down the mountain. Ka-boom!

We packed our tent and bags in four inches of new snow. Boom! We felt totally exposed, almost running down the ridge with our bloated packs. Boom! By the time we reached Paradise, 6,000 feet below Camp Hazard, it was still raining bear cubs and cougar kittens, before the thunder finally subsided. It didn’t matter that we were soaked. This was flat ground at last. I don’t know when they paved Paradise and put up a parking lot, but this one looked absolutely gorgeous that day.

Scott, my partner on the Kautz, was a strong ice climber from Boston, though he told me he’d never been on a glacier before. Let’s just say he was inspired. Within a few years, he’d become one of the most competent alpine climbers I’d ever shared a rope with. In 1992, he successfully reached the summit of Mount Everest. And many more great peaks after that. As for myself, I went on to become a reasonably adept Cascades duffer, finally reaching the summit of Rainier several years later via the standard route from Paradise.

Okay, then. Back to that footbridge over Van Trump Creek.

I discovered later that the predecessor of this bridge was blown to smithereens during the Van Trump debris flow in October 2003. The flow occurred after a rainy couple of weeks, resulting in a sudden release of water, rock, and sediment from high on the mountain. It began with rockfall near Camp Hazard (of all places) at the 10,500 foot level and increased in size from there.

An estimated 350,000 cubic meters of material flowed down the course of the creek, spilling tons of boulders across the road at Christine Falls and into the Nisqually River. Fortunately, the event happened at night and no one was hurt. Splinters of the footbridge were later found in the river plain a half-mile downstream. (A highly readable study of the debris flow is available here.)

That was twenty years ago, almost to the day. Maybe it’s a good thing we waited.

Chugging up the trail along Van Trump Creek, we're looking into the deep gash below, a continuous cataract of noisy water, tumbling over numerous falls and begging for photos. Above us are steep walls of forested basalt, sometimes exposed in bent and twisted colums. We’ve missed the wildflowers, of course, but the autumn colors of red and gold are brilliant among the evergreens.

The trail steepens to an upper crossing of the creek below a modest series of falls, photogenic in their own right. A brand new steel bridge here was also knocked out by the 2003 debris flow. The remains of the structure were never found.

We cross on a foot log, as the trail diverges to the West Fork of Van Trump Creek. We are now just steps away from the main show at Comet Falls. I've seen the pics, read about this place for decades. And suddenly we’re here. Holy cow. No, it’s better than that. I give it a holy mountain goat.

We've timed it perfectly. The entire falls, close to 400 feet in height, includes a 320-foot free-falling portion that does, in fact, resemble the tail of a comet. The falls are brightly lit and framed by a sloping green meadow, the path of seasonal avalanches and/or sporadic debris flows from above. Countless decaying tree boles appear to have been sheared off by the force of whatever it was that got ‘em. Near the base of the "comet," the morning glow treats us to a misty rainbow, violet to green to orange.

We relax a while, till the sun becomes a tad too warm on my back and I'm ready to move on. But not before a couple we meet from Vancouver offers a few tips on exploring their side of the border near our home port in Bellingham. Paddle to Widgeon Falls, he suggests. Anytime of the year will do.

We mush on. At a fork in the trail, right goes up to Van Trump Park, a subalpine expanse sure to be dwarfed by another 8,000 feet of rock and ice rising to the summit. But we go left, descending to a crossing of the West Fork before traversing above the brink of Comet Falls. Even if you’d never seen the falls, you could tell from the void beyond the brink that something big was happening on the other side.

Another fork in the trail. A small sign warns of active bees and wasps ahead. We meet another couple here, this time from Port Townsend. They consider their options. Lucky for us, we're turning right to trudge up another meadowy ridge. We find no bees. We’re here because I’d heard that Mildred has a point and we’d like to know what her point is all about.

The path dissects a flatish meadow, then becomes way steep, before suddenly we're on top. We shuffle to the brink of a 1,000 foot drop-off where the view is stupendous. Then we crane our necks at 8,500 feet of sheer rock and ice towering above us. Barren except for a few patches of green between the cliff bands. Mountain goat country. And sure enough, borrowing Mitch’s binoculars, I spot a lone goat grazing impossibly among the cliffs.

Spires of crumbling basalt stand before us, above the great chasm between us and the goat. Great tongues of white ice, the mother of water, hundreds of feet thick, drape Tahoma’s summit and the higher slopes, defying gravity, defying words.

Despite a smattering of fresh snow from the last front a few days ago, I can easily make out the serpentine form of the Kautz Glacier slithering downward from Point Success at 14,114 feet. Scott and I were just a few hundred feet shy of that when we were nailed by that thunderous snowstorm.

Camp Hazard lies below a wide split in the glacier, with ice cliffs perhaps 200 feet high threatening to come crashing down. You hope that when the teetering seracs, building-sized blocks of slowly moving ice, tumble with a crash in the night, that they plummet to one side of the ridge or the other. The absence of frozen debris on the crest of the ridge offers some comfort that that is the case. Nevertheless, from inside the tent at midnight, the booming sound of falling ice was memorable, to say the least.

I cannot imagine the deafening roar of a mile-long section of the Kautz Glacier releasing all at once. But that’s what happened in October 1947 after another rainy spell. The resulting debris flow was ten times larger than the 2003 Van Trump event, and it buried the road to Paradise under nearly 30 feet of rock and mud.

Today, we safely ponder past adventures and gravity’s tricks from a safe and sunny perch atop Mildred Point.

So who is this Mildred, I wonder? Later, I search the internet for an answer, but fail to find one. No one seems to know. I find a publication listing placenames for Mount Rainier. Mildred Point is listed, but the source of the name, it says, is unknown. Has history forgotten Mildred? Someone must know, right?

At least we’re able to confirm one thing: Mildred does indeed have a Point.

Mitch decides to begin the downward trek as I wrap up my notes and check the time. I've been sitting here for 80 minutes. Looking up once more, I scan for the fearless goat, shoulder my pack, and turn away from this magnificent mountain.

More on the first ascent of Mount Rainier (Tahoma)

Edmund Meany, a botany professor and president of the Mountaineers climbing club from 1908 to 1935, authored Mt. Rainier - A Record of Exploration, published in 1916. The work includes Hazard Stevens’ translation of the advice given to him and Van Trump by their Indian guide, Sluiskin, prior to their epic first ascent. Here’s a snippet:

“Your plan to climb Takhoma [Mount Rainier] is all foolishness. No one can do it and live . . . At first the way is easy and the task seems light. The broad snow-fields over which I have often hunted the mountain goat, offer an inviting path. But above that you will have to climb over steep rocks overhanging deep gorges where a misstep will hurl you far down—down to certain death. You must creep over steep snowbanks and cross deep crevasses where a mountain goat could hardly keep his footing. You must climb along steep cliffs where rocks are continually falling to crush you, or knock you off into the bottomless depths.

“And if you should escape these perils and reach the great snowy dome then a bitterly cold and furious tempest will sweep you off into space like a withered leaf. But if by some miracle you should survive all these perils the mighty demon of Takhoma will surely kill you and throw you into the fiery lake . . .”

Read about our next day’s adventure, the Tatoosh Twofer (Summits #39 and #40) here.